Saturnalia was an ancient Roman festival in honour of the god Saturn, held on 17 December of the Julian calendar and later expanded with festivities through to 23 December. The holiday was celebrated with a sacrifice at the Temple of Saturn, in the Roman Forum, and a public banquet, followed by private gift-giving, continual partying, and a carnival atmosphere that overturned Roman social norms: gambling was permitted, and masters provided table service for their slaves.

The poet Catullus called it “the best of days”. It was the Roman equivalent to the earlier Greek holiday of Kronia, which was celebrated during the Attic month of Hekatombaion in late midsummer.

In Roman mythology, Saturn was an agricultural deity who was said to have reigned over the world in the Golden Age, when humans enjoyed the spontaneous bounty of the earth without labor in a state of innocence. The revelries of Saturnalia were supposed to reflect the conditions of the lost mythical age, not all of them desirable.

The Greek equivalent was the Kronia, which was celebrated on the twelfth day of the month of Hekatombaion, which occurred from around mid-July to mid-August on the Attic calendar.

The ancient Roman historian Justinus credits Saturn with being a historical king of the pre-Roman inhabitants of Italy:

The first inhabitants of Italy were the Aborigines, whose king, Saturnus, is said to have been a man of such extraordinary justice, that no one was a slave in his reign, or had any private property, but all things were common to all, and undivided, as one estate for the use of every one; in memory of which way of life, it has been ordered that at the Saturnalia slaves should everywhere sit down with their masters at the entertainments, the rank of all being made equal.

Although probably the best-known Roman holiday, Saturnalia as a whole is not described from beginning to end in any single ancient source. Modern understanding of the festival is pieced together from several accounts dealing with various aspects. The Saturnalia was the dramatic setting of the multivolume work of that name by Macrobius, a Latin writer from late antiquity who is the major source for information about the holiday.

In one of the interpretations in Macrobius’s work, Saturnalia is a festival of light leading to the winter solstice, with the abundant presence of candles symbolizing the quest for knowledge and truth. The renewal of light and the coming of the new year was celebrated in the later Roman Empire at the Dies Natalis Solis Invicti, the “Birthday of the Unconquerable Sun”, on 23 December.

The popularity of Saturnalia continued into the 3rd and 4th centuries AD, and as the Roman Empire came under Christian rule, many of its customs were recast into or at least influenced the seasonal celebrations surrounding Christmas and the New Year.

Public Religious Observance

Ruins of the Temple of Saturn

The statue of Saturn at his main temple normally had its feet bound in wool, which was removed for the holiday as an act of liberation.The official rituals were carried out according to “Greek rite” (ritus graecus). The sacrifice was officiated by a priest, whose head was uncovered; in Roman rite, priests sacrificed capite velato, with head covered by a special fold of the toga.

This procedure is usually explained by Saturn’s assimilation with his Greek counterpart Cronus, since the Romans often adopted and reinterpreted Greek myths, iconography, and even religious practices for their own deities, but the uncovering of the priest’s head may also be one of the Saturnalian reversals, the opposite of what was normal.

Following the sacrifice the Roman Senate arranged a lectisternium, a ritual of Greek origin that typically involved placing a deity’s image on a sumptuous couch, as if he were present and actively participating in the festivities. A public banquet followed. The day was supposed to be a holiday from all forms of work. Schools were closed, and exercise regimens were suspended. Courts were not in session, so no justice was administered, and no declaration of war could be made.

After the public rituals, observances continued at home. On 18 and 19 December, which were also holidays from public business, families conducted domestic rituals. They bathed early, and those with means sacrificed a suckling pig, a traditional offering to an earth deity.

Io Saturnalia

The phrase io Saturnalia was the characteristic shout or salutation of the festival, originally commencing after the public banquet on the single day of 17 December.

The interjection io (Greek ἰώ, ǐō) is pronounced either with two syllables (a short i and a long o) or as a single syllable (with the i becoming the Latin consonantal j and pronounced yō). It was a strongly emotive ritual exclamation or invocation, used for instance in announcing triumph or celebrating Bacchus, but also to punctuate a joke.

Private Festivities

The head of the slave household, whose responsibility it was to offer sacrifice to the Penates, to manage the provisions and to direct the activities of the domestic servants, came to tell his master that the household had feasted according to the annual ritual custom.

For at this festival, in houses that keep to proper religious usage, they first of all honor the slaves with a dinner prepared as if for the master; and only afterwards is the table set again for the head of the household. So, then, the chief slave came in to announce the time of dinner and to summon the masters to the table.

Saturnalia is the best-known of several festivals in the Greco-Roman world characterized by role reversals and behavioral license. Slaves were treated to a banquet of the kind usually enjoyed by their masters.

Ancient sources differ on the circumstances: some suggest that master and slave dined together, while others indicate that the slaves feasted first, or that the masters actually served the food. The practice might have varied over time, and in any case slaves would still have prepared the meal.

Saturnalian license also permitted slaves to disrespect their masters without the threat of a punishment. It was a time for free speech. In two satires set during the Saturnalia, Horace has a slave offer sharp criticism to his master. Everyone knew, however, that the leveling of the social hierarchy was temporary and had limits; no social norms were ultimately threatened, because the holiday would end.

The toga, the characteristic garment of the male Roman citizen, was set aside in favor of the Greek synthesis, colourful “dinner clothes” otherwise considered in poor taste for daytime wear. Romans of citizen status normally went about bare-headed, but for the Saturnalia donned the pilleus, the conical felt cap that was the usual mark of a freedman.

Slaves, who ordinarily were not entitled to wear the pileus, wore it as well, so that everyone was “pileated” without distinction.

The participation of freeborn Roman women is implied by sources that name gifts for women, but their presence at banquets may have depended on the custom of their time; from the late Republic onward, women mingled socially with men more freely than they had in earlier times. Female entertainers were certainly present at some otherwise all-male gatherings.

Dice players in a wall painting from Pompeii.

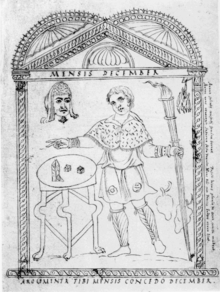

Gambling and dice-playing, normally prohibited or at least frowned upon, were permitted for all, even slaves. Coins and nuts were the stakes. On the Calendar of Philocalus, the Saturnalia is represented by a man wearing a fur-trimmed coat next to a table with dice, and a caption reading: “Now you have license, slave, to game with your master.” Rampant overeating and drunkenness became the rule, and a sober person the exception.

Gift-Giving

The Sigillaria on 19 December was a day of gift-giving. Because gifts of value would mark social status contrary to the spirit of the season, these were often the pottery or wax figurines called sigillaria made specially for the day, candles, or “gag gifts”. Children received toys as gifts. In his many poems about the Saturnalia, Martial names both expensive and quite cheap gifts, including writing tablets, dice, knucklebones, moneyboxes, combs, toothpicks, a hat, a hunting knife, an axe, various lamps, balls, perfumes, pipes, a pig, a sausage, a parrot, tables, cups, spoons, items of clothing, statues, masks, books, and pets.

Gifts might be as costly as a slave or exotic animal, but Martial suggests that token gifts of low intrinsic value inversely measure the high quality of a friendship. Patrons or “bosses” might pass along a gratuity to their poorer clients or dependents to help them buy gifts. Some emperors were noted for their devoted observance of the Sigillaria. In a practice that might be compared to modern greeting cards, verses sometimes accompanied the gifts.

Martial has a collection of poems written as if to be attached to gifts. Gift-giving was not confined to the day of the Sigillaria. In some households, guests and family members received gifts after the feast in which slaves had shared.

On The Calendar

Drawing from the Calendar of Philocalus depicting the month of December, with Saturnalian dice on the table and a mask (oscilla) hanging above.

As an observance of state religion, Saturnalia was supposed to have been held sixteen days before the Kalends of January, on the oldest Roman religious calendar, which the Romans believed to have been established by the legendary founder Romulus and his successor Numa Pompilius. It was a legal holiday when no public business could be conducted. The day marked the dedication anniversary (dies natalis) of the Temple to Saturn in the Roman Forum in 497 BC.

When Julius Caesar had the calendar reformed because it had fallen out of synchronization with the solar year, two days were added to the month, and Saturnalia fell on 17 December. It was felt, however, that the original day had thus been moved by two days, and so Saturnalia was celebrated under Augustus as a three-day official holiday encompassing both dates.

By the late Republic, the private festivities of Saturnalia had expanded to seven days, but during the Imperial period contracted variously to three to five days. Caligula extended official observances to five. The date 17 December was the first day of the astrological sign Capricorn, the house of Saturn, the planet named for the god.

Its proximity to the winter solstice (21 to 23 December) on the Julian calendar was endowed with various meanings by both ancient and modern scholars: for instance, the widespread use of wax candles could refer to “the returning power of the sun’s light after the solstice”.

Historical Context

Saturnalia underwent a major reform in 217 BC, after the Battle of Lake Trasimene, when the Romans suffered one of their most crushing defeats by Carthage during the Second Punic War. Until that time, they had celebrated the holiday according to Roman custom.

It was after a consultation of the Sibylline books that they adopted “Greek rite”, introducing sacrifices carried out in the Greek manner, the public banquet, and the continual shouts of io Saturnalia that became characteristic of the celebration. Cato the Elder (234–149 BC) remembered a time before the so-called “Greek” elements had been added to the Roman Saturnalia.

It was not unusual for the Romans to offer cult (cultus) to the deities of other nations in the hope of redirecting their favor, and the Second Punic War in particular created pressures on Roman society that led to a number of religious innovations and reforms. Robert Palmer has argued that the introduction of new rites at this time was in part an effort to appease Ba’al Hammon, the Carthaginian god who was regarded as the counterpart of the Roman Saturn and Greek Cronus. The table service that masters offered their slaves thus would have extended to Carthaginian or African war captives.

The association between Christmas and Saturnalia is further supported by the existence of another Roman holiday, Sol Invictus, gradually absorbed by Christmas. Sol Invictus (“Invincible Sun”) celebrated, on December 25, the renewing of the Sun King and was linked to the winter solstice. Constantine, was raised in this cult of the Unconquered Sun God, and he had a hand in turning Roman culture toward Christ and away from paganism. The first reliable historical evidence of Christmas being observed on December 25 dates from his reign.

Conclusion

So as, Christians, we readily and comfortably acknowledge that the date, traditions, and long-term history of Christmas are not connected to the pagan holidays of Saturnalia and Sol Invictus. Yet, like a family celebrating Bible Costume Party on October 31, it’s the people celebrating who decide what the celebration means.

Christians of centuries past chose December 25 as the day to celebrate the birth of Jesus Christ, the true “Unconquered King.” The use of this date continues today. Christmas and Saturnalia may be historical neighbors with indirect connections but, at the end of the day it is only speculation that one is the same as the other.

Christmas was started for the purpose of celebrating Jesus Christ’s birth and even though it has changed through the years we as Christians need to keep it about Jesus. Our focus has to be our Savior and King. Let us not forget about what’s important and that is being with family and Glorifying His name forever.

God Bless,

MyBibleQuestions

As a christian, I have to insist that nowhere in the Christian scriptures one can find a hint of the first Christians (even in Rome) doing anything about commemorating Jesus birth. In fact there is less than a handful of passages in the holy scriptures where there is mention of celebrating a birthday and none are Hebrews nor Jews. There are also ample arguments around that Jesus cannot have been born on December 25th nor even close to that date. Most classic example is that on that date you won’t find shepherds in the evening because it is the beginning of Winter. Jesus as an adult always directed the attention to his Father and never to him (one example is his public prayer before resurrecting Lazarus). Humility would not have allowed him to draw any form of attention to him year after year. He always glorified his Father Jehovah for everything so as to be the perfect exemplar of the life of a Christian.

“They are no part of the world, just as I am no part of the world.” – John 17:16 (longest recorded prayer of Jesus)

Thanks for allowing me to express my views in this matter.